cars

you might think I'm crazy

I hate loud noises.

As a child, I would cower at the sound of a barking dog. Like that dog, I whimpered at the sound of fireworks. Like that same dog, I trembled at the sound of thunder. They say we dislike what is most like us. Maybe that’s why I don’t like dogs. Only seven sentences in, and I’ve already digressed.

Then again, any unwanted noise is a peeve I don’t want to pet. The sound from someone’s headphones next to me on a plane. A neighbor playing his music a bit too loud. I don’t mind the sound of rain, but wind against the window is where I draw the line - and the blinds - to try to block out the thought of the damage potentially being done to the hundred year old house in which we live.

Three of my least favorite noises share a common source: a loud muffler, the sound of an engine revving, and the screech of the tires. Perhaps this stems from my general apathy and major boredom1 when it comes to cars - the vehicle: my affection for The Cars remains. I believe I’m in the male minority when I say that I have zero interest, beyond basic transport, in making cars a part of my life.

We inherit habits, traits and predilections from our fathers. My dad wasn’t into cars. Neither was his dad: after a stroke restricted his ability to use the right side of his body, my grandfather’s Cadillac - he did have a taste for luxury - was fitted to allow the use of his left leg to manage the gas and break. An unconcern for cars is a trait - one of many - that I’m proud to have inherited from my dad’s side regardless of whether it was nurture or nature.

Our cars mostly got us there and back again. They were mere conveyances. This differs from my mom’s side of the family with a cousin retaining his father’s Corvette obsession, though we both retain our mothers’ father’s hairline, or lack thereof. I’ve heard my cousin is building his “Garage Mahal” as a place to finish his restoration projects, or at least 95% of them. Yes, he still lives in/on Long Island.

Even though we weren’t into cars, they provided moments that became memories. The faux-wood-paneled station wagon carried my brother and I around in the ‘80s. I mostly got car sick in the backseat. The Renault Encore hatchback, due to a mechanic pulling the reverse plug instead of the oil drain, lost its ability to retreat, which is ironic for French car. I got my license shortly after the driver’s seat of our Mercury Sable Wagon, whose paint started peeling like a bad sunburn, became a rocking chair. While I cannot imagine this was safe, it was quite comfortable, and aligned with my grandfather’s penchant for luxury.

My first car was my dad’s old Mercury Topaz - the one with the automatic seat belts - which was, unlike its name implies, red. Senior year, I would drive my brother and a friend or two to and from high school. After one track meet, we attempted to make our way to a Chili’s which had just opened in East Haven. Instead of making a left out of the lot to head west, I took a right which would extend the trip a bit. I commented that I should have gone the other way. I checked my mirrors to see if our friends were following us and proceeded to slam into the back of the Ford Probe which, living up to its name, penetrated the back of another car, driven by a teammate on his first drive with a learner’s permit. Feeling tightness in my chest I was taken to the local clinic further east of us; my brother and our teammates were picked up by a mom who took them to Chili’s. That Awesome Blossom wasn’t going to eat itself.

Despite being a few years B.C. - Before Cellular - my dad somehow got in contact with me knowing I was at a clinic two towns east of where we lived and picked me up. He worked in New Haven at the time, and it would have been smarter had I asked to go to one of the local hospitals there. He made sure I realized that. He was livid, it showed, and is a trait I have also inherited that my kids see periodically. But other than some bruising - in my chest from from tensing up in the crash and my ego - and a scrap heap-destined Topaz, I was fine. In fact, as in Fitter Happier, I am more likely a patient, better driver, as a result.

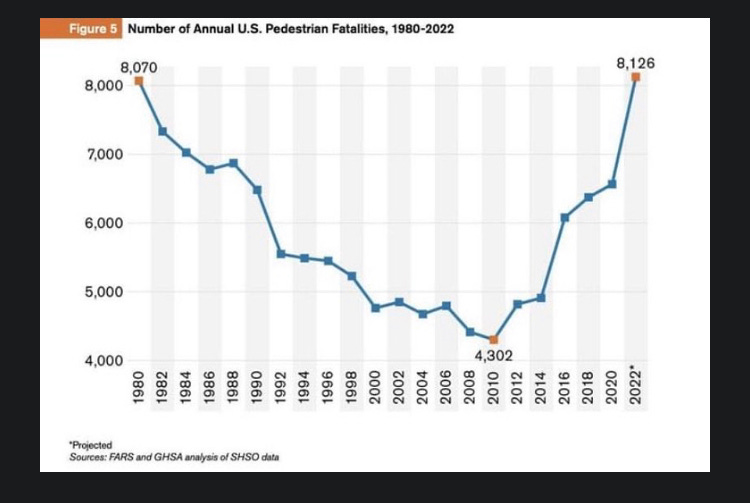

This cannot be said for most of those on the road today. Blinkers are optional, stop signs suggestive, red lights districts of unsafe (inter)sections. Maybe this has always been the case, but I hazard people now are more distracted and short of attention than ever. How can one be expected to wait three seconds at a stop sign before proceeding if one can’t even spend two seconds before scrolling to the next poison pill in one’s social media feed or checking who texted a thumbs up emoji to a gift you sent at the prior light? And while correlation is not causation, Facebook’s mobile app was released in 2012 which was also the year smartphones surpassed 50% of the US mobile market.

Look what else started happening in 2012:

It doesn’t help that the average vehicle size has increased since 1999, when the most popular car, a Toyota Camry, weighed 2,998 pounds and today weighs 3,310 - an increase of 10%. But this isn’t the most popular car today. The most popular today - the Ford F-series - ranges from 4,275 pounds to 5,757 pounds - 42% and 92% increases from 1999’s most popular car’s size. Our cars, like our waist lines, have expanded which like Parkinson’s law about work and time, may be at play here: our waist lines expand to the car allotted. In addition, that fellow driver’s car getting better means my has to be bigger, too, to keep me and my family safe. It’s perpetual auto-motion; bigger begets bigger. This is also why people can’t park within their spaces’ white lines.

At the same time, cars make our wallets lighter: it now takes an average American 26 weeks to buy a used car and 43 weeks income to buy a new light vehicle. Light is a relatively broad spectrum as it includes any vehicle under 8,500 pounds: from sub-compacts and hatchbacks all the way through trucks, minivans and SUVs. It turns out, it’s not that the price of cars have gone up that much, it’s that more of us are buying cars at the bigger end of the spectrum.

I was a math major, so indulge me for a moment for some calculations. In 1999, the year I crashed my Topaz, the median American salary was $36,476 (household $42,228), the average cost of a used light vehicle was $8,828 and new was $20,170. That equates to 24% and 55% of a median salary respectively. Today, the median salary in is $58,136 (household $74,580), the average cost of a used light vehicle is $27,028 and new it’s $47,943. That equates to 46% and 82%.

Why is this? Let’s start with the most popular car in 1999, the Toyota Camry which cost $19,444 in 1999, or 53% of the median salary. But you’ll recall from earlier that this is not today’s most popular car. That’s the Ford F-Series, which comes in at a base of $34,585 which is nearly 60% of today’s median salary. One could say that it’s because of processing chips and parts shortages on new cars, but that’s not really an excuse: In 2023, a new Toyota Camry is $26,320 or just 45% of today’s median salary which is 1000 basis points less than 1999.

I’m a man, so I’m supposed to love cars. Men are more loyal their car of choice than their sports teams, though many could be the same name: Vipers, Chargers, Mustangs. Men give their cars women’s names and talk about their sexy curves and headlights. We love the thrill of speed in our Chevy Corvettes, Porche 911s, and Audi S4s. We love joy riding, the wind in our hair - present company excluded. We love the ability to haul heavy things. Our favorite cars aren’t cars at all but trucks; our Chevy Silverado “like a rock, standing arrow straight” - no euphemism there from Mr. Seger, I swear. Readers will know that I love to peacock, which should make me a great lover of cars with all the feathers in their tails. But I’m indifferent at best showing little interest in using the car as muse for a hobby. Those who read the last post know about my complete ignorance to the joy that so many find in NASCAR. I have never personally changed the oil of my car. I have never personally rotated the tires on my car. If it wasn’t for the tire pressure warning light, I would forget to put air in my tires. But I can parallel park, on either side of the street, though I do need the music turned off and the everyone completely quiet if doing so with people in the car.

I think men also like cars because they are the original anonymous comments section of the internet, where you can rant and scream as loud as you want about what’s going in your life as you travel down the highway, fellow drivers thinking you’re just rocking out to some Trans-Siberian Orchestra. With me, it could be both things. Speaking of ranting on the internet, I was initially intrigued by Tesla, but I don’t support government subsidies for billionaires who complain about taxes and take their toys and move to Texas.

That said, there was a time I took an interest in cars and something very specific about that interest that still sticks.

Twenty years ago, I bought (read: went into debt to own) my first car: a MINI Cooper with a 6-speed manual transmission. I learned how to drive stick in the parking lot of the dealership north of Hartford Connecticut after taking delivery of the car. After a few laps around the lot, I felt confident enough to make it the 50 miles home to my parents, which was mostly on the highway. That highway on that rainy afternoon happened to provide ample bumper to bumper traffic, the perfect opportunity to perfect my stick shift skills. Stalling (only) three times felt like success. I parked my green with white racing striped Cooper/peacock in the driveway of my parents’ house.

I loved that MINI Cooper. It hugged the curves. It drew looks. Despite its size, bucket seats provided Max Headroom, even for a long-torsoed man like me. I took the time to install an AUX cable input for my iPod - the one with the tactile touch wheel - as this was before Bluetooth was standard. I would drive from my parents in Madison to Hartford for work, upshifting down the arrow-straight parts of Route 79 before downshifting up along Lyman Orchards. The manual gear shift responding like the Cars’ lyrics - with me it’s touch and go.

Driving that MINI Cooper in the early aughts wasn’t too different than driving up Snake Road2 just a few years prior. Like most teenage boys in suburban America in the late-90’s, there wasn’t much to do other than going to the movies, going to the beach, heading to the football game on Friday nights, heading to the diner, working a summer job, or heading to the rope swing on the edge of town. That sounds sinister; it’s not. It was mostly harmless - a story for another day - but to get there, or anywhere, one needed a car, or more broadly, access to a driver’s license.

My wife doesn’t have a driver’s license and while she is an exception to our generation, she would have good company in our children’s. When we entered high school in 1995, 64% of 16-19 year old teens had their license; at the current trends, when our oldest enters high school in two years, it’s very likely that 64% of 16-19 year old teens will not have their license: less than 40% did in 2021. Uber and Lyft are a tap away for teens; parents snowplow - a new transportation-themed term for parents beyond helicopter - their previously age-appropriate shuttle service through college. I’ll concede that some good comes from this: traffic deaths are down, drunk driving is down, teen pregnancies are down. But what is lost when kids switch lanes from childhood to adulthood without being a teenager with the freedom and risks it entails?

For the purpose of the narrative, I recall what I’ll claim to be my first trip in a senior’s car during the fall of freshman year. We had just finished up cross country season and were heading to the Town Green to play ultimate frisbee. I was offered the opportunity to get a ride from the backseat of a yellow Jeep Wrangler - a stick shift, of course - with fur-lined seats. As a tall kid, my placement in the backseat was a bit of a contortionist act with my knees in my neck. I don’t remember much about the frisbee game. It may not have even been frisbee. But I remember feeling like the coolest fucking kid our side of the East River.3 It wasn’t the car, it was what it represented: freedom, growing up, being accepted into part of a group. Lyft, Uber, and - I say this as one - parents provide none of those things.

Back to the MINI Cooper, after an electrical issue opened the moon roof during an evening snowstorm serving as a catalyst, I ended up trading it in for a used Volkswagen Golf Diesel TDI - still a stick shift; the $439.57 payment each month I was paying for a taste of Britain made by a German company was just too much. I took the car with me when I moved to Brooklyn but the most common use for was to practice my parallel parking, moving it at night to avoid alternate street parking four days a week. One morning after a night’s snow, I came out to head to a meeting in New Jersey to find my car gone. I circled the blocked a few times thinking I parked it somewhere else but it was no where to be found. I called the police, a stolen car report was made. While it wasn’t fraud, I won’t lie: I was happy to no longer have to worry about finding parking. Plus, a stolen car meant an insurance payment that would cover the rest of the car loan.

The investigation continued for a few months, with the detective providing updates, albeit without success. My insurance company made a decision with the car being a total loss. Days before receiving the payout, I received a call from my grandmother. She received a call from a Brooklyn number claiming that they had my car and that they needed me to pick it up. A pound, located three blocks from me, had towed the car from in front of a driveway the prior winter, which they claimed I parked directly in front of. There must have been the remains of an icy snowbank making me think it was just a curb. Instead of a payout, I paid out to the tow pound - in cash - over a thousand dollars to get my car out of the lot. I took it as a sign and three months later, I sold my car to a dealership in Connecticut.

A week later I received a call from the dealer saying that my car was reported stolen. The saga concluded with the detective, who had to reopen my case, closing it as resolved as found. As a bonus, with my car previously reported stolen the parking ticket had already been cancelled.

A ZipCar membership, local taxis, and ride share apps got me through the rest of my years in New York City, and my first few up in Westchester. Our family’s transport today is a used, 2016 Subaru Outback. When we moved up from the city, we lived here without a car for 3 years, buying it when we got a parking spot in our building - two spots to be exact, though we only needed the one given my wife’s aforementioned lack of driver’s license. It had 70,000 miles and change and over the last five years, we’ve put on another 40,000. Yes, it has dents. Yes, the rear view mirror on the driver’s side is missing a plastic covering. Yes, it doesn’t get great gas mileage, especially with most of our driving done on local roads. Yes, it is currently in the shop at a dealership4 determining whether the cracked catalytic converter - whatever that is - is covered under warranty or whether I’ll have to pay $4,000 to fix it.5 But, as my wife says, it is a safe, reliable, family car, and who better to trust than the perennial passenger?

Speaking of perennial passengers, you might think that I would be all about self-driving cars. “So much more time you could spend reading books!” Alas, my friend, you forget my car sickness. As my wife says, I turn my head to fast and I’m prone to motion sickness. But my motion sickness is a bit of a super power: it forces me to say hello, and maybe even have a conversation, with my Lyft driver. And while I don’t have one now, I love a manual transmission and what it represents: touch. We continue to lose touch these days: with people, to newspaper ink, to actual printed books, and to understanding when it’s time to shift and have better control of the car during a snowstorm or to simply experience. We don’t even have to turn the ignition to start our trips anymore, with push-button start and auto-starters quickly becoming the norm, all so we can be a few degrees warmer or cooler when we get in our cars. We have what Michael Easter calls in his book of the same name, a comfort crisis,6 and while I’m an advocate of staying medium, we our default state gets softer.

While she’s never had an episode in the back of our car, my oldest daughter, like me, suffers from motion sickness. As a three year-old, taxi rides in Manhattan frequently required an empty plastic shopping bag for her sickness to be contained therein. Should that happen in the Outback, since I was born in/on Long Island, I have a car wash subscription with our local chain - just having them vacuum the kids’ detritus from the backseat once a week is worth it. Her motion sickness provides a great excuse not to allow her to use a device while riding. Instead, she and her sister typically stare out the window, ponder quietly, or open up like dandelions on a summer morning, a cannonade of chatter with thoughts about the day, questions about the past and future.

When asked how The Cars got their name, Ric Ocasek’s bandmate said: "It was easy to remember and it wasn't pegged to a specific decade or sound. The name was meaningless and conjured up nothing [emphasis mine], which was perfect." When I started writing this piece, that’s exactly how I considered cars: meaningless, conjuring up nothing. But for all my outward disdain, in the end, cars do provide meaning not for what they represent - status, money and masculinity - but for what they are - transportation and freedom. Transportation both to my destination and a vessel to conjure the past; freedom not just of the open road but to make one’s own decision, to be a little reckless, to stay out a bit too late, to suffer consequences and to grow up.

But I’ll never buy a Tesla Cybertruck.

Singing, whatever and ever, amen. Apologies to Ben Folds but I couldn’t resist.

Must be said with an Australian accent like Steve Irwin. I guess you had to be there.

Not the one you’re thinking; the one that splits Madison from Guilford, Connecticut.

I received news during the writing of this piece that, thankfully, it is covered. Good thing I went to the dealership.

I received news during the writing of this piece that, thankfully, it is covered. Good thing I went to the dealership.

As an affiliate of Bookshop.org (read: they are not Amazon), project kathekon will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. You’ll also help a local independent bookstore in your community.

I'm going to say no thanks to that Tesla Cybertruck as well.

I related a lot to this, I'm not a car guy either. No interest at all. I'm 34 can't drive. My dad couldn't drive until he was 38, so I've got a bit of time yet!