My wife could tell something was wrong the moment I walked in the TV room. Yes, despite reports to the contrary, we own a TV - four in fact - though I seldom use one alone. I wasn’t even sure something was wrong. But my eyes did. My eyes gave it away.

They usually do. I’ve had a terrible poker face since I was a little kid. When I was ill, my hazel eyes would turn a shade greener. On the plus side, my mom would know in a second if I was sick, letting me stay home from school. On the down side, my mom would know in a second if I was not sick, putting me on the bus to school.

When I had a crush on a girl, and I was once again rejected when asking her to the dance, my mom would know the pain I was feeling while staring blankly at the TV. If I failed an assignment, I couldn’t hide that fact when my parents got home from work. They knew something was up. And I’d confess.

Each descendant of my father has inherited what we lovingly call Keimbrows. Keimbrows are like two very hungry caterpillars telling a story through facial expressions. They are thick in both their height and thoughts they convey. My nieces and my daughters have them. My oldest daughter in particular. In fact, when combined with the freckles just below the eyes, she is the spitting image of a soon-to-be-teenage version of me.

But unlike me, she has adapted to hide certain emotions typically displayed by her patrilineality.1 Which is where the honest lights come in.

My father had a gift that came with Keimbrows as the eyes below could see the honest lights in his sons’ and daughters’ eyes. When my brother and I would stretch the truth or know we were in the wrong, he would look at us, and calmly command: Let me see the honest lights. Without fail, his assessment would yield a result with marksman-like accuracy. While I fail to ask the question often enough of my own kids, perhaps I should. There is something revealed only through the line of questions, like a criminal taking the stand, that under a lack of targeted duress remains hidden. Perhaps this would have helped when asking her whether she completed her assignments during the recent quarter to avoid a shock upon opening her report card.

But that's for another day. Today, we continue with what happened after we confronted her, as her eyes told the story not through her Keimbrows but through her tear ducts: my daughter, like me as a child - and let's face it as a middle-aged man - is prone to crying. But, again, this is not about her, it's about me.

In the audience of a recent showing of In The Heights at our community theater - they run three different musicals a year - my youngest leaned over and asked if I was crying. Of course I was. How could one not what with the lyrics and story and music from the mind of Lin Manual Miranda?2 She snickered, but after years of crying as a highly sensitive boy, being made fun of incessantly, I've become capable of not taking offense. It’s part of who I am.

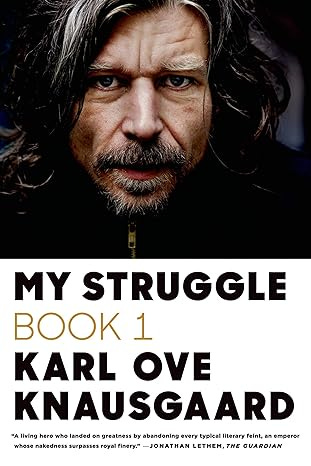

I like to think I’m not the only man capable of tears. I recently read Karl Ove Knausgaard's epic autobiographical novel My Struggle (yes, the name is a shock, but stick with me). And while his ability to make the mundane beautiful continues to stick with me, it is his continued examples of getting misty-eyed, of crying, of bawling, of ugly crying that put me front and centered into the narrative. Spanning his life to date across six volumes - and 3,600 pages - there remain few stretches without references to salinity-saturated streaks forming rivets down his cheeks. And sure as shit he has some expressive eyes.

I recently read another book by another Norwegian, Knut Hamsun, who had his own terrible associations to Germany in the 1930s and 1940s. We'll put those to the side for a moment and separate the art from the man. In 1890, he published Hunger, about a struggling writer who roams in and out of homelessness around Kristiania (modern day Oslo). Knausgaard references Hamsun - both the Nobel-worthy literature and the fascist racism - in My Struggle but it wasn't until I read Hunger that I saw the opening for Karl Ove to write about his own tears. The unnamed narrator states:

I went on crying all the way down the street, felt more and more sorry for myself and repeated over and over again a couple of phrases, an exclamation that brought more tears on just as I was trying to stop them: Christ, I'm having such a hard time!

And again, for emphasis adds, "Christ, I'm having such a hard time!"

As men, we're supposed to be stoic, without emotion in the face of danger, sadness, grief and joy. We were taught at a young age that crying is for wussies, wimps, babies, mama's boys. And while I hear things have changed - I don't have boys - this is still the mantra3 we hear from those like Andrew Tate, Josh Hawley, Ben Shapiro and [INSERT DIP SHIT POLITICIAN HERE] with the lone except of Jordan Peterson - he's cool with it. The Cure sang about it, Frank Ocean wrote a book entitled it and Hillary Swank stared in a movie named it: Boys Don't Cry. And try as I might, I can't stop myself from telling my daughters - channeling my best Kindergarten Cop impression - to stop whining.4

Yet I find myself alone, but on a crowded train bound south, on the verge of tears. I've felt this draw towards moistening eyes, like a saturated sponge ready to be squeezed and relinquished of its tepid water. I feel others' gazes, their eyes on me. Do they know how I feel? Do they feel it, too? Do they see it just like I can see the pain in their eyes, too?

I don't think I'm alone feeling the pandemic and remote work and Zoom meetings have completed ruined my ability to make eye contact with fellow humans. It was one of the first things I noticed in the weeks, months and years since: this complete inability to lock eyes while conversing with those outside my immediate household. I realized - likely far too long for it to make a difference - that video conferencing may have been the culprit. And not for the reason you may think. It’s been written that the slight delay between speaking and the screen responding to it and the person beyond that screen responding, that it creates a type of seasickness on the brain.

But that’s not my struggle - my struggle is that I myself am on that screen too. Where in life, other than in front of a mirror, are you constantly watching yourself as you do something? It's the visual equivalent of hearing your own voice in a video playback, but in slightly slower than real-time. I remember as a 25-year old - 18 fucking years ago - listening to myself give a presentation on health insurance - it was about high deductible health plans if memory serves, on which I was to be judged before going to open enrollment presentation fairs with a construction company going full replacement away from the traditional HMO, in an effort to save money by passing more of the burden on to the presumably working poor, but this is not about that - when I heard my own voice.

It wasn't the voice itself that was most off-putting, or at least not the most off-putting - because it was. It was the faint linger of the lisp I had as a kid. A lisp that I was made fun of by the neighborhood kids, by the school bullies, by myself. A lisp that I thought I vanquished after years of speech therapy. But no, there it was, in the crispish audio of an early aughts digital video, for all of my classmates to hear and for my eyes to witness as I listened in horror. For while we listen with our ears we understand with our eyes. And my eyes gave it away.

What is that you express in your eyes? It seems to me more than all the print I have read in my life.

Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

I feel deeply. It is a burden I bear, but perhaps I should see it as a badge I get to wear. It is a feature, not a bug, as they say in Silicon Valley. I like to think we remember what we feel most deeply. If the body keeps the score, the eyes provide the color commentary.

Birthdays are one such occasion for feeling deeply. When I was four, a boy ate my birthday cake before it was time - I'm also very punctual, a rigid rule-follower. And I cried.

When I was thirteen, we traveled to New York City for the day. It was an opportunity for me to eat a large sandwich at a delicatessen, to buy my first cologne (Polo Sport, purchased at Saks Fifth Avenue), and to truly see my first homeless person. While we lived in an affluent town, the concept of homelessness was not new to me. But coming face-to-face, human-to-human, and eye-to-eye with a man and his misfortune tore at me. His legs stopped just below the knee, signs of earlier amputations, and he had crutches. He wasn't old but he wasn't young either. Probably about my age now. While I don't recall his voice, I'm sure he asked for help. How did this happen to him? How could this happen to him? Did he not have any family? Why did he deserve to be in this position? It wasn't fair. There were no answers. And I cried.

As I tell this story to a colleague over a hotel dinner tonight in Baltimore, I could feel tears welling up. Thirty years later to the day, and I was right back there. As I share more details I remember other times I felt similarly. After a night out at a bar - Annie Moore's, the old one, in Midtown Manhattan - in my late 20s spending too many $20s on beer and friend food, I stepped out into the bracing cold of winter to walk back towards the D Train to Brooklyn. I passed a homeless man, a cardboard box for shelter, for warmth, for any semblance of security. I got to 5th Avenue - yes, the same one - and turned back east. Reaching for my wallet, I took out two $20s. Here, you need this more than I do. And I cried.

When I see what I perceive to be loneliness, someone by themselves at a restaurant, I feel an immense sadness. Some would say that I shouldn't feel badly, that this is only perpetuating their loneliness, by making them feel less than, making them feel my pity. But it's not pity I feel. It's not that they are less than. They are me, in all my times of loneliness, of feeling like an outsider.

On two recent trips to my hometown, I had this same feeling. My daughters and I sat at a table at Lenny and Joe's Fish Tale, and noticed an old man sitting alone nearby. My attention was taken away from the conversation we were having by the questions this gentleman’s presence demanded. Was he a widower? Did he have family nearby? Did he have friends? Did he choose to have lunch alone? Was this not a choice at all? His eyes told me it wasn't a willing choice.

I could have said hello, made conversation, but I didn't want to intrude. Instead, upon leaving, I asked the front cashier if I could pay his bill for him. They obliged. My kids asked why and I told him that I felt sorry seeing him there all alone, and the least I could have done was make him feel like someone cared enough to think of him. I didn't want him to know and I don't write this now to take credit for this. I write this because I didn't do the human thing: I didn't look in his eyes, I didn't say hello, I didn't ask him his name. I didn't make a connection; I made a transaction.

A similar opportunity presented itself a few months later. Same town, same restaurant, same tables. But this time it was an older couple. They looked like they were struggling to decide what to get, what they could pay for. As our meal finished up, I again asked the cashier if I could pay for their meal. They again obliged. As we left, my kids again asked the same questions as before. And again, I answered the questions. But I didn't look the couple in the eyes, I didn't say hello, I didn't make them feel human, I didn't make a connection. I made another transaction.

Something similar happens when I see a man providing security for a conference I am at wearing a sport coat with the thread still connected in the tail. I see it, I feel badly, yet I do nothing about it, too scared to approach a stranger with a piece of advice. Something similar again happens when the waiter gives my credit card back, says thank you Mr. Keim, mispronouncing my name, and I reply, you're welcome, without any correction.

But if that same waiter charges me a lower amount than he should, I correct him. Both of which happened this week while at dinner on my birthday (which I also didn’t mention to my colleague). I've returned lost wallets to restaurant hostesses, and turned in found money in the surf at the beach to the lifeguard in the chair.

When my Lyft driver drives too slow or too fast or too scattered, I say nothing. Sure, I'll give him a lower rating, and comment as to why, but I'll still give him a standard 20% tip - he still needs to make money and my inconvenience should not impact his ability to feed a family.

I'm not a better person for any of this, it's just who I am. I don't want people to feel like they're the lesser in any situation whether it's correcting something about their appearance or having them lose out on money that was and still is theirs.

Since I was a boy, I've hated asking strangers questions. I don't like to inconvenience people. Asking a waiter for a menu - god forbid a restaurant still carries paper versions with their shitty QR code process still in place since the pandemic - asking for assistance from a shopkeeper, asking a doctor about symptoms I have, asking a colleague, a friend, my wife, my brother, my parents for help. I hate confrontation even when the confrontation is just between the neurons in my head as they duke it out between the ears.

And all of this becomes apparent when you look at my eyes. Beware, the Eyes of March are upon us. While we share his type of birth, unlike Caesar who didn't see it coming this past Friday 2,068 years ago, I've seen it coming for the last 43 years ago this past Tuesday. By it I mean the sadness, the otherness, the loneliness, the embarrassment, the less-than-ness, the insecurity, the imposter-ness in those around me. But as was likely the case with Caesar, my eyes show the signs of shock and sadness and betrayal and loss that come with the first stabs of guilt, of pain, of anguish, until the last. Et tu, Brute? Indeed.

As a child, my father would call me Smiling Jack and Dimple Dan. He would sing about Irish eyes smiling. I've been told all my life - even as a child - that my eyes give the appearance that I shoulder the weight of the world like Atlas. Caesar bore the weight of the Roman world. Look where that got him.

As I set to finish this piece on the train ride home from Baltimore, the words of Hamsun's unnamed narrator in Hunger come to mind.

But write I could not. After a line or two nothing came to mind; my thoughts were elsewhere and I was unable to wind myself up for any distinct effort. Everything affected and distracted me; everything I saw gave me new impressions.

My eyes see the world; they allow others to see me. Like the vows of a wedding, to have and to hold, for better, for worse, in sickness and in health, in good times and bad, for richer for poorer, so long as we both shall live.

She’s learning about Punnett squares at school so this is a topic of recent discussion in the house.

Yes, of course I cried during Hamilton, too.

Is this a pun?

Whinging to the Brits.

I've noticed the unsettling eye contact thing too post pandemic - almost like we all need to be trained how to "look me in the eyes when you're talking to me," all over again.

On transaction v. connection, I'd encourage you to cut yourself some slack. You did something. A better way to think about it could be "how could this be even more impactful next time than it was this time?" and then, if you decide to go the way of transaction, or smile, or whatever...cut yourself some slack again.

By the way - one of my absolute favorite things in the world is to go a nice restaurant, sit at the bar, and eat all by myself.

Happy birthday!

Deep, do you find the lack of contact to be because of your own confidence, shyness, or lack of words to say? Or are yo torn between who you are and who you want to be?