snow

informer, of a life well-lived

The first flakes for this piece started more than two years ago.

I was shoveling our shared driveway after an evening snow deposited six inches. Not powdery and dry - if you can call it that - snow, but wet, stick-to-your-clothing, throw-out-your-back, give-you-a-heart-attack-if-you’re-a-typical-out-of-shape American, snow. I thought about how I would relate it back to my child hood; how shoveling snow was a good thing; how we should welcome the opportunity to do physical labor; that we’ve lost the joy to be found in working up a sweat; and what all that means to being a man today. I thought about the winter ahead and taking each storm as an opportunity to build up the piece, word by word, snowflake by snowflake.

But then we didn’t get more than an inch of snow for almost two years. And there’s nothing like a fresh snow to rekindle past thoughts.

Last week, the weather forecast called for an 80% chance of 10 inches of snow for this past weekend. They then changed it to a 30% chance of mixed precipitation. Then to a 60% chance of rain. Then a possibility of an inch of snow. And then another call for rain. Finally, on the day their final forecast called for mixed precipitation, it started snowing. And while we didn’t get the initial 10 inches of snow, we ended up with 7.6”, which is pretty close to the expected value of an 80% chance of 10 inches of snow. But then again, the weathermen, with all their forecasting capabilities, get it wrong more often than not and weren’t right in this instance. Proof enough for me that AI has a lot of catching up to do. Technological dig and digression achieved.

Following the weather is nothing new for me. I was one of the first to grab a free version of Dark Sky and would know to the minute what the weather would be, with deadly accuracy. That is, until Apple bought - and absolutely ruined - it. I recall elementary school winters, with school mornings tuned to the Weather Channel - which somehow, despite being bought by IBM recently, had more accurate forecasts in the ‘90s - Local on the Eights to see how much snow we were due to get to enjoy, or rue, depending on the school delays - or closures! - being announced on the local radio station. Madison, falling in the middle of the alphabet, would be called after the neighboring towns of Clinton, Durham and Guilford. If one had at least a delay, it was all but certain we’d have one, too. For many of those years, we also had an early warning system: my mom was a teacher in our town and when the phone chain would kick off with one teacher calling two more until the school staff was informed, we’d wake up early to listen for the phone ringing before the sun also rose.

Growing up, in my house - or just outside, in the drive- and walkways specifically - shoveling was man’s work. Or at least boy’s work, once my brother and I got to that certain age.1 My dad had this monstrosity of a contraption called an alpine shovel sleigh he picked up at the local hardware store. Its claim: to be very effective in gravel driveways - we couldn’t afford pavement until our teenage years - as it was intended to glide just atop the gravel removing the snow as you pushed like a teenage-powered snowplow leaving the gravel, and a layer of snow, behind. Our driveway had a slight pitch to it, and with gravity as our co-pilot, we successfully cleared the snow. The gravel provided grit for the tires of the car even through the remaining snow, so it did the trick. It would take until the next thaw to see the gravel left in the grass.

I still remember one storm that dumped a few feet. Our driveway had a wall of boulders that retained our front garden closets to my dad’s side of the garage. For this storm, shovels were no match, so we hired a snowplow to clear it. The plow left a mound of snow, 6 feet high if it was a foot,2 next to the garage. And with our shoveling duties officially furloughed for the day, we set our plastic shovels to work on the mound. A tunnel from one side was met with one from the other. A turret of sorts was produced, perfect to startle our dad on his return home from work; snowballs ready-made and waiting for an ambush; metal garbage can shields for protection against his counter.

The following weekend, with temperatures staying below freezing since the storm, we took to the street. Our house was just above the cul-de-sac, French for “place for boys”. The Dover Lane Gang, as our dad anointed us, was made up of kids, mostly boys, spanning ten years from oldest to youngest. During any given school year or season, our membership numbered between eight and twelve. It was in this cul-de-sac that the real snow plows had done their work, creating five snow banks roughly quinquesected by four neighbors’ driveways and the street straightening its way back up the hill. We cashed in on this opportunity and proceeded to dig out more tunnels and turrets. It took the better part of a Saturday to build out two forts. Snowball fights ensued.

What I’ll say was late that same winter and approaching my twelfth birthday, at a Boy Scout winter camping trip, we were again bestowed with 12 Inches of Snow - both meteorologically and musically: an album by the same name by the Great White North’s Snow, born Darrin O’Brien, and his song Informer was about to hit number one on the pop charts in the US.

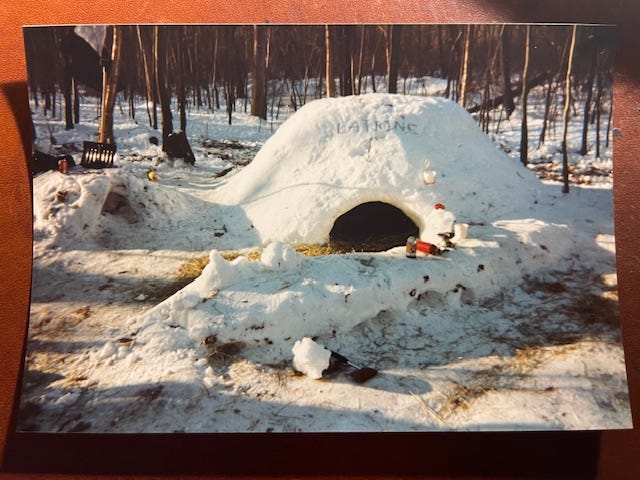

Back to camping. Instead of the requisite tent and winter sleeping bags, two fellow scouts and I decided to build an igloo to sleep in for the night. We set to work, shovels somehow in hand - I’m not sure whether we planned ahead and brought them or if a parent ran home to get them - and started piling a mound of snow. Once satisfied with its height, we took to carving out an entrance, complete with mounds on the sides to block the wind, and proceeded to clear out just enough space for three boys to sleep in. A father suggested we poke holes in the roof in a few places to prevent us from suffering from inhaling too much of our own carbon dioxide and various deleterious (and delirious) effects that could ensue. Smart man. Our evening abode was not complete until we placed sticks spelling out the word “latrine” above the entrance transforming it into a commode. We slept comfortably and warmly, the snow acting as both an insulator above and a firm mattress below. We were proud of our work.

While Governor of the Empire State, in a speech made in the City of Big - or Broad - Shoulders, a reference to the last line of a poem by Carl Sandburg, Teddy Roosevelt implored:

I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph.

As he went on, while he expanded out from the individual to society as a whole to make the case for what was more or less imperialism,3 Roosevelt’s emphasis on what the individual could stand to gain from such a life came from experience. Theodore was a sickly, asthmatic boy, who was advised to stay behind a desk; instead he took up boxing, hiking, rowing, was known to take point to point walks in straight lines going under, over, or through whatever he faced, and plunging (Teddy) bear-assed naked into the Potomac in winter as President. Put another way, he was David Goggins and Wim Hof combined.

As Emerson said, “an unexamined life is not worth living”. I used to think this was a lie. And it is. And while it was Socrates who (supposedly) said these words, they are no less true. As I examine my own, I realize that true comfort and honest pride can only be realized through hard work.

As kids, work can be play. We get sandy digging sandcastles and holes to bury ourselves at the beach; we build up a sweat shoveling snow in order to can build forts; we rake leaf piles so that we may jump into them. As adults, we just see work.

But work - in and of itself - is worth it. In physics, we learned that work is force multiplied by displacement, or distance traveled. While I don’t have the alpine shovel sleigh, when I become a human plow, I work. We have a fence in our backyard and in order to keep the driveway clear, when I have to throw some of the show over it I add into that equation the force of gravity. And I work. Just as my heart rate rises as a result of a weighted squat, an hour shoveling snow provides an ideal mix of cardiovascular and strength training I pay good money to do at the gym. And like the gym it can be enjoyable, too.

During this past week’s snow storm, after she was disappointed that I had already finished shoveling the drive and front sidewalks, our youngest asked to help clear a path off of our deck. I left the kids’ shovel for her and went to the gym. On my return, she showed me - and with pride - the result of her work. And it was good work.

When we left for school the next morning, she stated that despite the darkness, she planned to play outside upon her return from after-school. I picked her up and she repeated the intent. I intimated that the cold and dark evening may be too intimidating. She disagreed; she’d put the outdoor lights on. “You can ask your mum when you get home,'“ was my reply.

After dinner, she made for the backdoor, snow pants and boots at the ready. She pleaded with me and wife to let her outside. We both said no; it was too late, it was too dark.

And I thought about this piece I had started after the first flakes fell earlier in the week. I thought about my own childhood. About the snow banks. About winter camping. About early dismissals. About two-hour delays turning into snow days.4

About how we would play in the frigid, frozen, front yard where the front porch lights reflected off the snow just right to crystallize our vision.

I thought ahead to the next day’s forecast calling for higher temperatures and with it significant rain, bringing an end to our first significant snow in 692 days.

“On second thought, go ahead. Just be careful.”5

I would have joined her, but I’m not a kid anymore.

And as I put the final touches on this piece, I turn and look out the window. It’s snowing. There’s work (I get) to do.

Eight.

It was.

Not great, Bob.

As was the case today, with a two-hour delay turning into a snow day. For them, not me.

The phrase just be careful has become rote vernacular when talking to my kids. It’s a habit I’m trying to break.