coins

paying it forward

The simplest things take you back.

While making coffee this morning, I reached for an over-sized container of Cafe Bustelo. Ground for ground, there is no better mass-produced coffee on the market. As I took the fine espresso grains out of the container and placed them into the drip-coffee maker - it was 4:45am, way too early to coherently make pour-over, and to be honest, I haven’t used the Chemex in years, its Mayor of Halloween Town-shaped face laughing at me from the top shelf - I thought it would make a great place to store coins.

Coins aren’t used, circulated, dropped and then found like the used to be. Canada abandoned their penny 11 years ago this past February. I can’t recall the last time I found a coin - heads up, no less - on the sidewalk. Pay phones don’t exist so there’s no more finding a nickel, or a dime and then a quarter, as the price of a call went up, in the return. The last time I remember taking a container - a metal Animal Cracker canister - of coins to the bank was when we lived in Manhattan, the change from the days’ cups of coffee emptied from my pockets every night with the sound of the remainders of the day hitting their previous days’ compatriots.

That coffee canister was metal, the coffee container I stared at that morning was plastic, and the coffee jars my Papa Primo used were glass. Folgers crystals and Sanka (do either of those legally count as coffee?) had previously inhabited them; my grandfather filled them with coins he’d find. He was a janitor at the local schools in Levittown, Long Island. When he would sweep the cafeteria floors, he’d reveal the change left behind by the students, teachers and faculty. They were mostly Lincolns and Jeffersons, with some Washingtons and the rare FDR sprinkled in. My brother and I would pick up coin sleeves from our local bank - an actual local bank with local roots and employees we knew by first name - and count out rolls of 50 cents worth of pennies, two dollars worth of nickels, five dollars worth of dimes and ten dollars worth of quarters, our hands awash with the scent of copper and various not-so-precious metals. We’d return to the bank with our bounty rolls to have their value placed in our accounts, the savings passbooks noting the deposit like a library book borrowing card. These are the types of memories my kids will never have with digital deposits made on their debit cards for (mostly) doing their chores instead.

Papa Primo was born in a city previously ruled by the Habsburg monarchy. Coins were scarce: his family was money poor but he was street - and seaside - smart. The way he described his native city of Trieste - home to Illy coffee and Generali Insurance, and a muse to James Joyce and Jan Morris - made it sound more like a quaint fishing village. In his broken English, he regaled stories of a childhood along and within the Adriatic.

As a boy, he would make his way to the dockyard. Boxes of produce would sit, the green rinds of the watermelons emitting their sirens’ calls. With stealth, strength and a bit of youthful stupidity, my grandfather would enter the water on the shore, dive under and, holding his breath, swim until he’d reach the dock. He’d climb up, and take a watermelon before diving back under water, breath held until he reached the shore. Largess secured, he’d break it open revealing the rose pink flesh tasting of equal parts sugary sweetness and stolen success.

Trieste sits on a sliver of land fought over by various countries and kingdoms for millennia. Born in 1923, my grandfather approached adulthood as Mussolini amassed power. Il Duce’s Blackshirts were met by partisans who rose up in resistance. My grandfather was one of them. He never shared stories of his attacks against true fascism, his watermelon appropriation serving as a suitable predictor of his capabilities. During one raid, he was caught, and sent to a prison camp.

It’s unclear - maybe his memory was fuzzy then or mine is now - whether he was in Germany or Austria or somewhere else entirely. I don’t recall exactly how long he remained but he escaped, though details again remain unclear as to how. He made his way to a farm in the Dolomite Mountains. At this farm, a family - German-speaking, if memory serves correctly - allowed him to hide in one of their outbuildings, likely a barn. They provided him with food and water, likely for weeks. Soldiers came and searched, but he was never found.

At some point, a bicycle was obtained. My grandfather left, grateful for the shelter and safety he was given, heading back to Trieste. This was not a simple journey for two reasons: mountains and brakes. Or, lack there of, as this being the early-1940s, brakes were not yet common on bicycles. The easy part was making his way up the mountain; the hard part was safely riding down the hill without a mechanism to stop his progress. My grandfather, with a fourth grade education, realized it wasn’t about how to stop that was as much of the problem as it was about merely slowing down.

He found a rope. And while this has the makings of a Paul Bunyan story - and while it is not, at least not exactly - my grandfather channeled his inner Paul Bunyan and chopped down a tree. And while this has the makings of a MacGyver episode - and while it is not, at least not exactly - he tied the tree around his waist and set off down grade. This allowed him to slowly make his way down the hairpin turns of the Dolomite Mountains. Eventually, the big branches of the tree would break off, increasing both the speed of his progress and the risk of injury, or even death. He’d somehow bring the bike to a stop, chop down another, fuller, tree, and repeat the process. He arrived back in Trieste.

The war eventually ended and while a gap in the narrative now presents itself, we pick up my grandfather’s story when he eventually joined the Merchant Marine sometime in the late-forties. He traveled throughout Europe’s Adriatic and Mediterranean coasts and out into the Atlantic Ocean. One of his trips had him dock just outside New York City whereupon he jumped ship and swam to shore. Yes, my grandfather was an illegal immigrant.

From there, he made his way to Manhattan. He somehow got a job as a dishwasher at John's of 12th Street. It didn't pay well, but with a job in hand, and a connection to the new world settled, he returned to Italy. He wanted to officially start in America the right way. He came back by way of steamer ship across the ocean to Ellis Island. As a huddled mass yearning to breathe free, he resettled in Manhattan.

It was while washing dishes at John’s that he met his wife - my grandmother - and they decided to start a family. I doubt they decided or had any conversation that would lead to a debate. Back then, you just had a baby. A girl - my aunt. And then another girl - my mom. At some point, they moved to Levittown. They lived on Center Lane in a red house with a detached garage. They had two more daughters.

It's unclear exactly when he started drinking. With his drinking came an even more booming voice, even louder laughter and sometimes even anger. I recall as a child being shown a hole in the door - it was one of those cheap hollow doors - that he had punched through. Inanimate objects being one thing, I never heard stories of any physical violence against the animate and I trust that this is the case.

With a wife who had her own setbacks and shortcomings, my grandfather worked and raised their four daughters in a three-bedroom house. Unlike other men of his generation and age, he engaged in their lives. He coached swimming at the local pool, his memories of the Adriratic attacks on watermelons translating into patient lessons. I don't have his patience. Three of his daughters went on to be Jones Beach lifeguards. As part of the inaugural female class, in fact. I write these words the day I finished reading The Power Broker, about the man who built that and many other state parks, a man with his own demons.

My grandfather worked hard. I don't recall a single moment I saw him complain. But I did. I complained about how loud he was. I complained about his dog, Nikki, who to this day remains a barking force in my hatred of dogs. And fear. I complained about the (Italian) Parmalat milk he bought - we drank 1% or 2% at home and full fat milk was something I soured on at an early age. I complained about the TV they had, black-and-white and no cable of course. I complained - or maybe just questioned - the oil stain on the wall behind the couch from where my grandfather would fall asleep (pass out?) while watching whatever the antenna allowed in with minimal static (Lawrence Welk most likely).

I complained about how he hugged us a bit too hard. I complained about his body odor. I complained about his car, its ceiling fabric peeling as it backfired when he put it in gear, my embarrassed self sticking to the vinyl seats as we made our way to the local pool. I complained about how he challenged us to get to the top of the high dive. I complained to myself as I jumped into the pool, failing to completely dive and doing a belly flop instead.

I complained about the lasagna he made. I complained about the Italian cookies he baked - the ones that looked like little bowties that he would store in large cardboard boxes labeled EGGS in big block letters. I complained about how hot his house would be in the summer. I complained about how his breath wafted of alcohol, though I wouldn’t recall him drinking the alcohol of which it smelled. I complained about, well, everything that had to do with my grandfather.

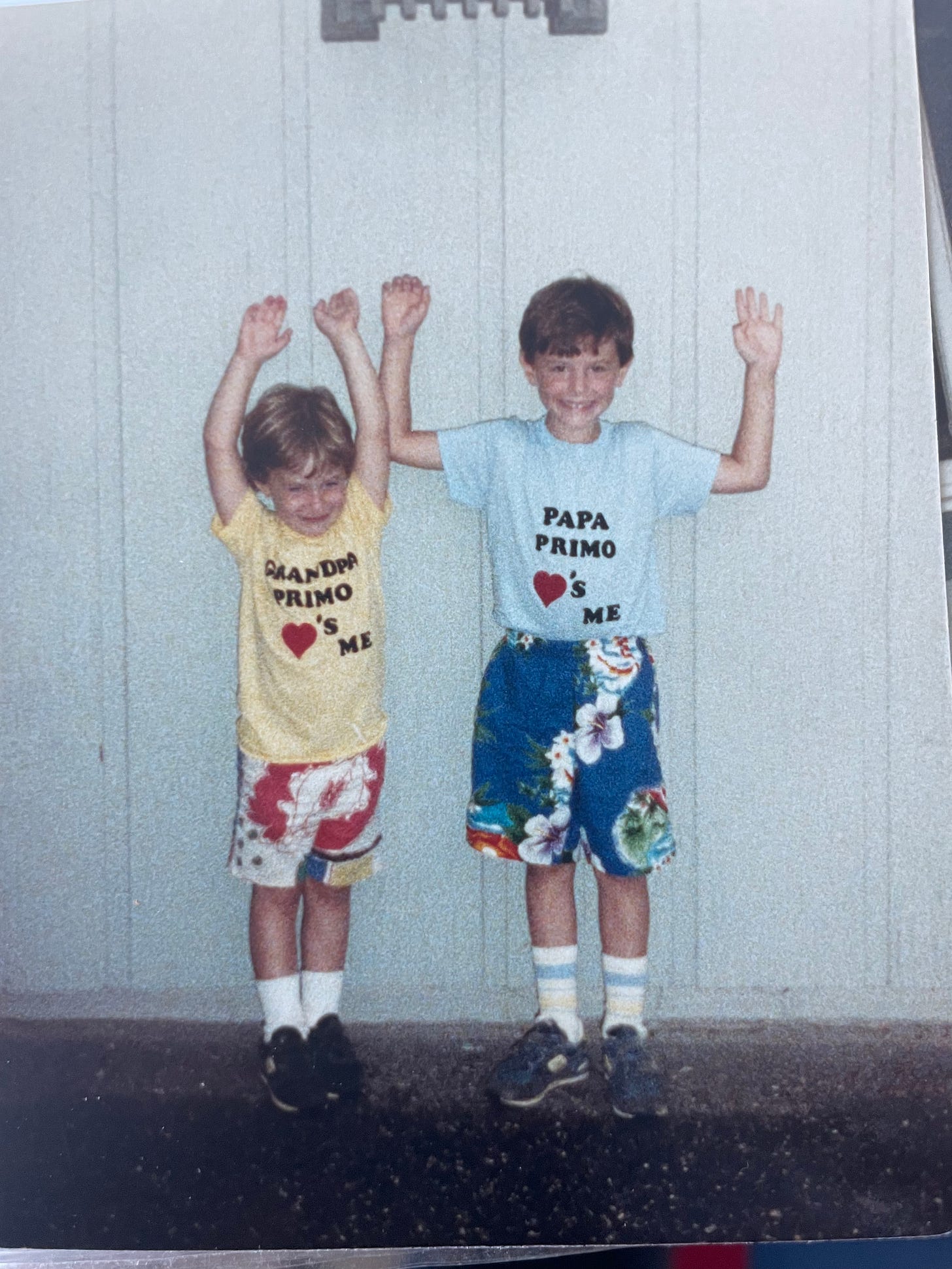

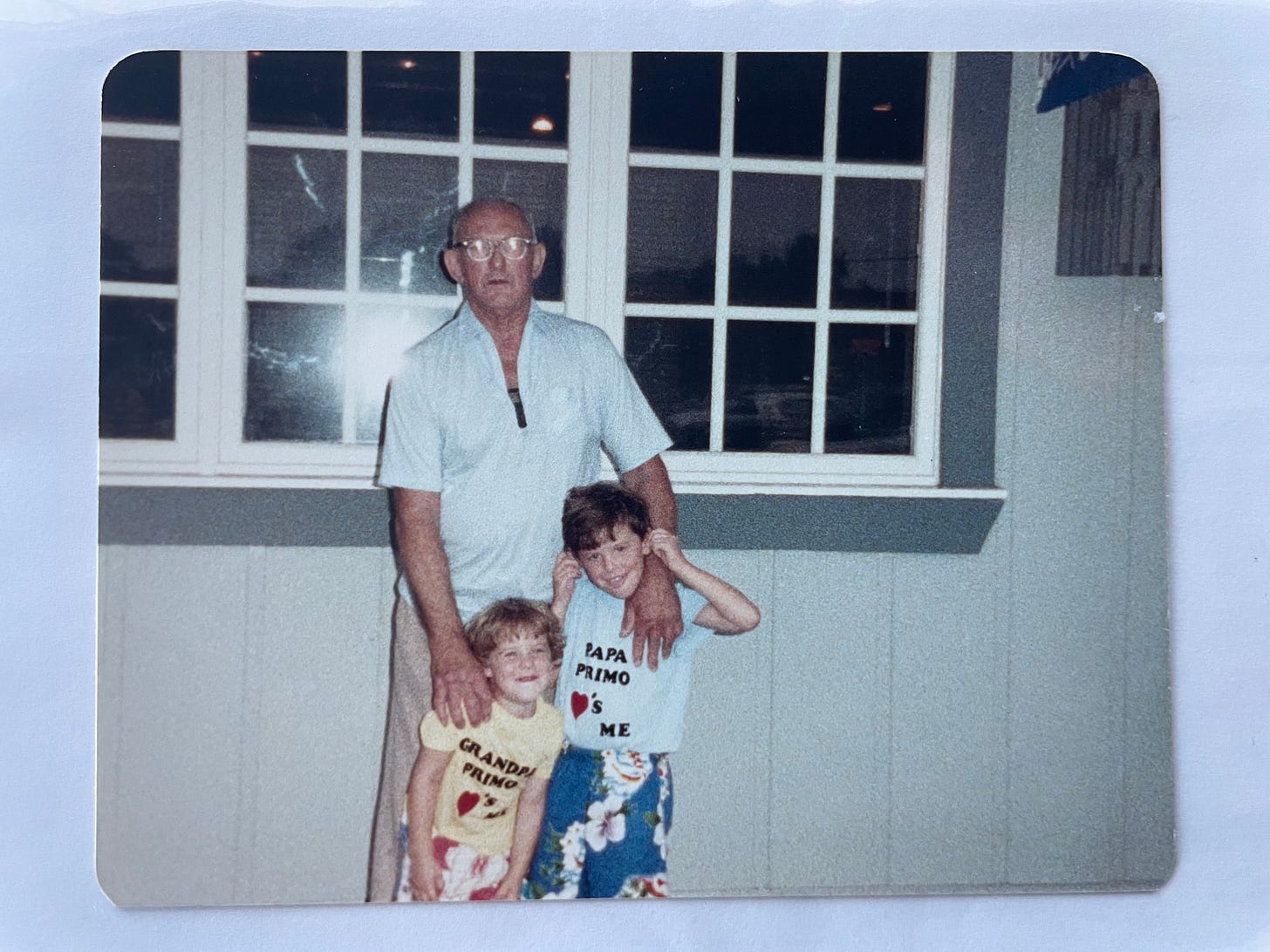

But as the t-shirt said, Papa Primo loved me. So where did my complaints come from? They came from my own prejudices, my own embarrassments, my own discomforts.

My grandfather died June 21st 1996. He was 63 years old. It was our last day of school. I had just finished 8th grade and returning from the shortened day of school, we faced the news that he had passed. He had been in the hospital for a few months. Cirhosis of the liver. When we last visited, his skin was yellowed. His liver was failing; his time was coming to a close.

I remember the day he died for two reasons: first, it was the day 10 of us were heading to the Allman Brothers concert at the Meadows up in Hartford; second, I don't recall shedding a single tear. My mother said that we should still go to the show as planned. It was to be my first concert. And it was. Throughout the show, I recall feeling both wonderfully happy and thinking I should feel profoundly sad.

At his service the following week, I walked to his casket. It was open. His skin no longer a waxy, jaundiced yellow - the mortician did good work - gave him the appearance of napping on the couch after a large plate of pasta and a few glasses of red wine. I was taken back to the meals we would have at Annabella's Restaurant.

We spent our Easters there. We'd start the meal with baked clams by the dozens. The tiny little fork used to separate the clam from the shell. A squeeze of lemon on the buttered bread crumb topping. We continued with garlic bread and a primi of pasta, followed by a secondi of chicken parmesan or veal marsala. To conclude with dolci we'd get the tortufo: it came in a little paper cup, a scoop of vanilla covered in almonds, crushed.

Those meals were filled with Papa Primo's booming voice, going from table to table saying hello to the patrons he knew and those he didn't. Never shy to show affection, he'd give his friends - both female and male - a large bear hug, for he was a large man. Around the table sat cousins and aunts and uncles, all reveling around the table revealing what family meant.

It was with these thoughts, standing facing my deceased grandfather, that I started, finally, to cry. For someone as quick to tears as myself, the catharsis had finally arrived.

As the months and years went by, there would be moments my grandfather's memory would come rushing back. My mom would make his stuffing recipe at Thanksgiving with copious amounts of fennel and Italian sausage and I would be back at his house on Center Lane. I'd be in an Italian bakery and see the cookies - were they pizellas? no, they were bowties - twisted and coated in powdered sugar and I'd see the box of EGGs whose label was a red herring. I bought the first Bialetti coffee maker I saw after renting my first apartment as a way to remember him. And nearly a decade after he passed, my parents, my brother and I flew to northern Italy: first to the Dolomites as a primo, then to Venice as a secondo, and finally to Trieste, our trip's dolce.

From all we were told, Trieste would be a small fishing village. It was not. The history of the fought-over city, the statue of James Joyce, the memorial to those Tito killed by throwing them in the caverns on the outskirts of the city, Maximillian's Mansion, were overwhelming. When we went to see the birthplace of my grandfather, we were met not with a hospital but with the ruins of a Roman structure: years after his birth, they discovered ruins that were excavated and preserved.

After my wife and I moved back to New York City, my aunt - his daughter - suggested we get her sisters, including my mom, my dad, my brother and my cousins together at John's of 12th Street for dinner. As we made our way through lower Manhattan, my mom shared the story of how her mom and dad met while he was a dishwasher there. She shared how she grew up right around the corner, her building now a basketball court. While the past may be paved over, or the past uncovered to reveal an even older past, we have our memories. If we don't tell our stories with others, how do we know who we really are?

Jan Morris wrote a book titled Trieste and The Meaning of Nowhere. It's a story of the city, its successes and failures, the hard times of its inhabitants. She refers to it as a "sweet melancholy" to which she returned throughout her life. She writes about how places - for better or worse - shape the lives and personalities and histories and memories of its citizens. While I can relate, so can my mother: she fears dying poor like her father did.

Financially, yes, he died poor. But he was not poor with life. Two of his daughters went to college, something no one in his or the previous generations within his family had done. He was an involved father, well ahead of his time, raising four girls with a wife who struggled throughout her life. He always made sure guests were well-fed, with wine glasses that were well-filled, and always sent people home with some of those cookies, or a slice or two of lasagna. He was generous with his time and with his spirit. And his spirits. The phrase street smart I use earlier doesn't do him justice. While he was money poor, he was life rich. He fought against actual fascists on their home turf to boot. For all his demons, he loved his family. We are all damaged in our own way. I hated him growing up and I hate that about myself. I let time go by without realizing the lessons I was learning.

I started this by saying how the simplest things take you back. I mentioned that it was a coffee can that took me back. But why wasn't it instead each coin I saw on the ground being the thing that took me back? Perhaps money - little money - was too close to home - his little home, the memories of which I tried to suppress. But as I've aged, I've noticed that I've not only inherited his hairline, and his predilection for alcohol, but his nose and his ears.

I am reminded of the final lines from the poem, The Mower, by Philip Larkin - a man with his own faults:

we should be careful Of each other, we should be kind While there is still time

Yes, our time was cut short by his alcoholism, but I cut it shorter while he was still alive. I was a shy boy, sensitive, quick to tears, fearful of loud noises and dogs. I'm not saying I should have "been a man" and toughened up to connect with him. Masculinity isn't just about brute strength. Perhaps there was a middle ground with him. I will never know. So I ask myself, on what would have been my grandfather’s 101st birthday: which relationships am I cutting short because of my own embarrassment, my own stubbornness, my own ignorance?

It’s time to pay it forward.

This is beautiful - and I love the quoted poem. Thanks for sharing.

And I have to say that my favorite line was "Back then, you just had a baby."

Thanks Jeremy for this touching resonating tribute.